The paintings of Ignacy Czwartos are haunted by unquiet ghosts of history. Or rather, many histories animate the paintings of this modern History painter: Polish history, European history, the history of art and the ineluctable history of Czwartos the man. The glorious and execrated dead populate his large canvases, standing shoulder to shoulder with the living, just as the achievements of the Old Masters can be juxtaposed with those of today’s painters.

Who is this Ignacy Czwartos?

Who is the painter of these pictures, which contain such provocative images and judiciously balance disparate references and modes? Ignacy Czwartos (b. 1966, Kielce) describes himself as a “modern Sarmatian”. With such a description, the painter intentionally invokes the mythos of the Polish national spirit. “Sarmatian” is a reference to the noble caste that ruled Poland in the late Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. The Sarmatians have their origins as the East-Slavic Antae, an equestrian people who came from the Pontic Steppe and migrated to the Baltic region in the Dark Ages. Although references to Sarmatia made by nobles of the Kingdoms of Poland and Lithuania have been considered spurious, analysis of weaponry and textiles in royal collections reveal designs common to those of the Caucuses and Persia.

From 1988 to 1993, Czwartos studied under Tadeusz Wolański at the Department of Art Education in Kalisz, part of the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań. The young painter’s work was championed by Jerzy Nowosielski (1923-2011). In footballing terms, Czwartos is a reliable team player: in 1995, he co-founded the Open Studio Artistic Association and Gallery (becoming the president in 2006), and the producer of book illustrations. He is unusually generous with his references and acknowledgements, including in his paintings friends, colleagues and wife Zuzanna, who are situated beside more publicly recognisable figures.

Czwartos works as both an abstract painter and as a painter of the figure, using highly schematised settings for semi-realistic figures. In the two genres the artist uses the same grounds and devices: muted colours, symmetrical geometric devices, smooth surfaces, absence of visible brush marks. Figures are generally taken from photographic sources, rendered accurately but without illusionism. Purely abstract pieces (small paintings and painted box sculptures) are muted in coloration and often small.

In his figural paintings, we meet Czwartos’s personal pantheon of artistic models, including Kasimir Malevich (1875-1935), Russian painter of Polish descent, as well as Mark Rothko (1903-1970), born within the borders of present-day Latvia. Added to these figures is Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), another patriarch towering over the field of Early Modernist abstraction. These artists (and others) appear in homage pictures, in which Czwartos acknowledges his spiritual debts. Self-Portrait with Abstraction (2008) has Czwartos in clothing based on Malevich’s late painting style, holding up a sign of Malevich’s emblematic Suprematist square.

The practice of making geometrical abstract painting, sometimes related to landscape conventions, has had the effect of honing Czwartos‘s aesthetic sensitivity. In a Czwartos painting including figures, the background panel, borders and framing devices are as carefully judged as the figures. Religious aspects of the painting of Mondrian and Malevich are well known; Rothko’s art is notable for its symmetrical characteristics, similar to those of icons. Many of the arguments made by theorists (including Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky) regarding abstraction relate to its capacity for spiritual revelation. It is therefore less surprising that it might be that Czwartos has become increasingly attracted to religious art. Mentor Nowosielski furnished Czwartos with the example of a living Polish painter who appreciated the potential of abstraction and the possibility of icon-painting as a living practice. The pair would exhibit together in 1995.

Mention must be made here of Polish painter Andrzej Wróblewski (1927-1957), whose non-naturalistic figural paintings commemorate Poles who died in World War II. It is not incidental that Wróblewski turned his back on the Socialist Realism of his early career to make more honest and difficult work that cut him off from former supporters. In 2014, Czwartos paid tribute to Wróblewski by portraying him (full-length) in a coffin, one of his paintings nearby. In 2023, the links between these artists were examined in a group exhibition held in Lublin.

You cannot always choose your team

In the most recent (and most complexly layered) phase of his work, Czwartos draws upon numerous pictorial lineages: religious painting, the abstract, Symbolism, History painting, heraldry and other areas, not all of them by any means “pure” fine art. Czwartos pays keen attention to Polish practitioners in each of these fields. In Kielce, Kielce Korona (2008) Czwartos painted himself wearing the yellow scarf of his favourite football team, Korona Kielce, indicating loyalty to the city of his birth. Colours and spatial division refer to heraldry (including sporting heraldry) and abstract art, mixing manners and hierarchy.

In terms of allegiance, through his art Czwartos asks us ”Where do you stand?”.

One pledges fealty in sport, in relationships, in art and in faith, although sometimes these are matters beyond elective affinity. Consequences of such loyalties shape our existence, both through internal commitment and external pressure, determine how we live and how we die. Limitation, like suffering, should not be futilely denied but instead accepted and comprehended.

Artists make their choices more publicly than most of us. When Malevich first pledged himself to Modernism and uncompromising abstraction, he was a member of a tiny vanguard movement in Imperial Russia. Later, historical circumstance would make Malevich a leader of the Soviet project to engineer New Man through transformation of the arts, before making him a politically suspect individual, monitored and marginalised. In contrast, Rothko’s route lay more directly (although not speedily) to wealth and acclaim through committing to abstraction; if his family had stayed in Latvia, Rothko’s fate could have been similar to Malevich’s or worse.

While Czwartos asks to whom we pledge allegiance, he also recognises that we are not self-determining atomised individuals. We are involuntarily bound to groups that influence (or determine) our existences. What religion we are raised in, what soil we are born upon, who are families are and what our era is, these are not matters we can alter, despite our capacity to distance ourselves in a limited manner. We are born into circumstances that form us. In aesthetics and ethos, an artist may choose to only a circumscribed degree.

Czwartos refutes the notion that we are entirely masters of our destinies.

History is neither clear nor linear – those staple contentions of Whig (or liberal Enlightenment) understanding of history – as borne out by the course of Poland’s history. The sudden shifts in Poland’s political situation – moving between the lodestones of Catholicism, monarchism, federalism, Communism, capitalism and globalism – refute the notion of history developing logically through irrevocable progress.

Ars Moriendi

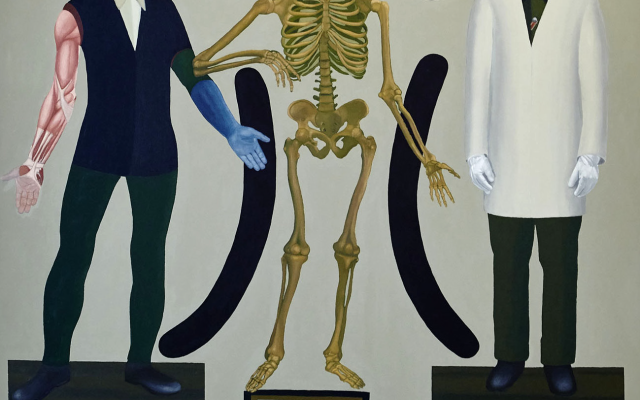

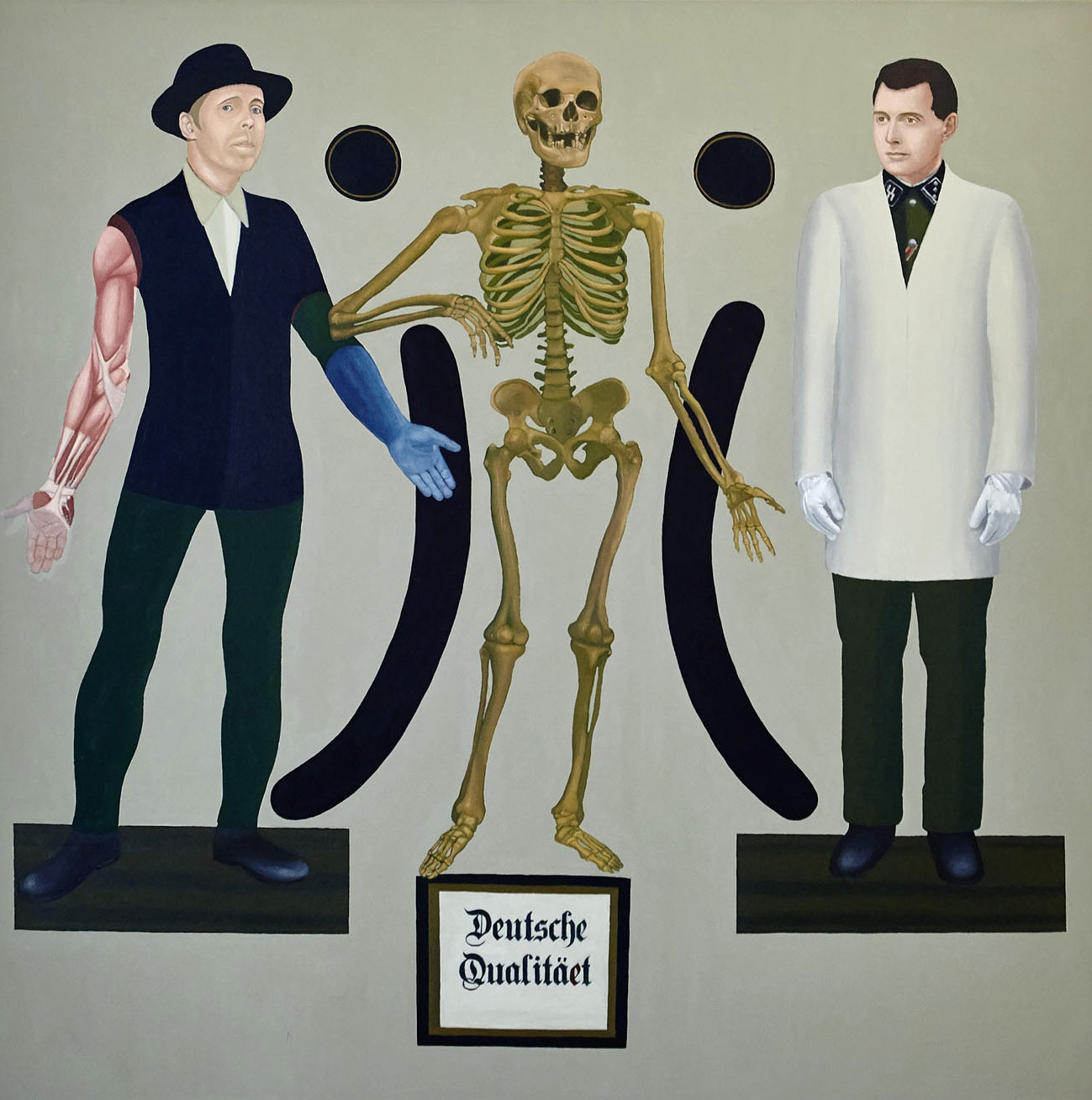

In the late 2000s, Czwartos moved from questions of artistic affiliation to Polish history. In complex allegorical paintings – large in scale, sometimes taking polyptych form – appear German soldiers and death-camp officials, from the occupation of Poland 1939-1945. In these pictures (that appropriate the post-painterly geometric aesthetic) there is a certain queasy wit apparent, with disparate figures juxtaposed to create scenes the resemble folk art and Baroque coffin portraits. Gunther von Hagens (creator of Body Worlds, which features chemically-preserved human bodies) is compared to Dr Mengele, the notorious anatomist who performed gruesome experiments upon death-camp inmates. SS death’s-head icons are accompanied by declarations in German (written in the Gothic script), that welcome viewers to the death-camp showers. Blue faces and hands in Czwartos’s art indicate proximity to death, recent or impending. Skulls and skeletons abound, as in illustrated Ars Moriendi treatises.

Ignacy Czwartos, Deutsche Qualitäet (Gunther von Hagens, Josef Mengele)

(pl. Niemiecka Jakość), 180x180 cm, oil on canvas, 2014.

Property of Center for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle.

Ars Moriendi (Latin: the art of dying) is the title of multiple devotional books of the late Medieval period that instructed the dying on how to achieve grace before meeting God. They treat death as a test of the pious Christian, a trial that can neither be ignored nor foregone, and which requires humility, honesty and fortitude to endure courageously. The unnatural stiffness found in poses of some of Czwartos’s subjects replicate those in devotional woodcuts and funereal portraits. The pre-Enlightenment conception of man receiving absolution from sin through the embracing of his subordinate mortal status is pertinent to the latest of Czwartos’s paintings.

The muted landscape colours of Czwartos’s early abstractions take on secondary supporting roles in these paintings. Czwartos is deliberate when he employs abstract elements to design pictures in the manner of devotional prints or altarpieces. There are also echoes of church memorials. The handling of paint is neutral, which increases the clarity and legibility of the imagery; sizes are well judged. The detached style – akin to that of René Magritte – renders Czwartos’s potent imagery all the more striking. Such troubling images need no exaggeration to intensify their emotional power.

The recent exhibition The Painter was Kneeling When Painting (2023, Zachęta Gallery, Warsaw) documented the full range of Czwartos’s modes and subjects. The title was not ironical; it indicates the artist’s reverence towards his noble forebears. (Of course, the artist might himself be sneaking a crafty glance at his own (potential) immortal glory, even as he wholeheartedly prays for others.) The coffin portraits memorialise notable men; Czwartos, in a time of artistic nomadism, voluntarily takes on the role formerly filled by guild painters, who were commissioned by burghers to immortalise civic leaders and clergymen.

The newest paintings on display in Warsaw – and soon to be displayed at the Polish Pavilion at the Venice Art Biennale – had strikingly stark imagery related to Polish history and the iconography of saints, martyrs and Christ. Alongside earlier paintings were Czwartos’s most difficult work: paintings relating to World War II (already described) and those about the Cursed Soldiers.

The Cursed Soldiers

In a series of paintings, commenced in 2016, Czwartos has depicted Poland’s “Cursed Soldiers” (Żołnierze Wyklęci). These were the Poles who fought first the German occupiers, then the Soviet liberators (who quickly became occupiers) and their Polish Communist allies. This campaign by patriots, liberals and Christians who sought an independent, non-Communist future for Poland, was ultimately doomed. The resisters were hunted down, killed in battle or captured (to subsequently face execution or lengthy prison sentences). Their activities were long suppressed and when mentioned publicly during the 1945-89 period, they were described as Fascists or bandits, descriptions which damned their memories and shamed their families.

The Cursed Soldiers were not only cursed by Polish Communists and Soviet occupying forces but also cursed – or damned – by history as “Fascist insurgents”. The Nazis have been taken as the ne plus ultra of evil by liberalists and socialists. So, when opponents of liberalism and socialism have been compared to Nazis, they have (by association) been implicated in tyranny and genocide. Hence, Polish nationalists supportive of democracy, monarchy, Church and Polish nationhood became “enemies of the people” and were subject to the practice of damnatio memoriae (Latin: damned in memory), with their names being erased from history.

Facing the might of the Polish state and its Soviet allies, the partisans were doomed to be dispersed, hunted down, imprisoned and executed. The rebellion was largely defeated by 1947. In 1951, the Polish secret police took seven imprisoned resistance fighters and tortured and executed them in Mokotów Prison, Warsaw. The last resistor was killed in a gunfight in 1963; thereafter, all mention of them was deleted from Polish public discourse. The story of the Cursed Soldiers has only been researched and discussed widely in the last decade.

Czwartos’s paintings relate to a history not yet absorbed by the population and respond to the rehabilitation of “enemies of the people” and, as such, are highly controversial. In effect, the post-war history of Poland is still being written.

No wonder the paintings – stark and vivid as they are – provoke strong reactions.

Resistance fighters in Czwartos’s pictures are painted from family or service-record photographs; sometimes they are treated collectively as family trees of the Nineteenth Century, with faces in oval frames, dates written below. Treter’s Eagle (pl. Orzeł Tretera) (2017) has the white Polish heraldic eagle populated by portraits of members of anti-Communist insurgents. Other sources Czwartos has used are the pathology photographs taken by authorities to document the executions and bodies of the insurgents. In Epitaph for Józef Franczak “Laluś” (pl. Epitafium dla Józefa Franczaka „Lalusia”) (2016), the last Cursed Soldier (who was decapitated after his death) is shown carrying his own head, like a martyred saint, accompanied by his killers. A priest who assisted the resistance flanks Christ in a modern altarpiece. Other fighters are symbolically depicted chopped into pieces; the faces are accurate depictions of known individuals, some from post-mortem photographs. The deaths are portrayed as inevitable as those of saints – predestined and necessary. It is only when man accepts that he is servant to a greater destiny that he can fulfil his historical function as victim, executioner or witness.

In some paintings, soldiers are portrayed as toy soldiers, not to belittle them but to indicate their relative powerlessness in the hands of forces more powerful than they. These depictions remind us that, uniquely in history, our generation is more familiar with soldiers as toys than as subjects for serious painting. Today, we are told that serious painting transcends quotidian description and specific place. In 1.2.3.4. “Żelazny’s” Soldiers (pl. 1.2.3.4. Żołnierze „Żelaznego”) (2008), Cursed Soldiers support the bodies of fallen comrades. The posthumous portraits recall the death photographs of Che Guevara and the coffin portraits of the Paris Communards of 1871.

By adapting and paraphrasing the iconography and armature of Polish devotional art (notably from the Baroque era), Czwartos can replicate in parallel fashion the symmetrical and hierarchical qualities of both abstract and religious art. In his paintings, Czwartos situates the Cursed Soldiers in a lineage of saints, martyrs and devout donors. They are the most recent additions to the canon of Polish patriots, albeit fiercely opposed by some Poles.

It is instructive to look at Czwartos in comparison to Jacek Malczewski (1854-1929), Polish Symbolist. Malczewski’s meditations on Poland’s character and future were painted predominantly before Poland’s independence, granted in 1918. Working from life, he transformed models and members of his family into mythological figures acting out scenes that retained ambiguity, whilst performing at an allegorical level. Czwartos’s mature oeuvre post-dates Poland’s independence from the Warsaw Pact in 1989; it is the dead who serve as models, through documentation photographs. These allegories that are as ambiguous as, but much starker than, Malczewski’s visions. Czwartos’s works exhibit an uncompromising acceptance of realpolitik. In Fish (Ryby) (2018), figures are chopped in chunks like fish for a stew – a motif drawn from Wróblewski; this dicing reminds us of Poland’s fate, which was to be carved into portions and devoured by neighbouring states in 1772, 1795 and 1939. Men, individually and collectively, are fated to suffer the vicissitudes of fortune independent of natural justice.

Malczewski sees men of his day taking up the challenge of adopting mythical roles to advance their nation; Czwartos sees the tragedy of men destined to enact roles imposed upon them by their nation, force majeure.

There is a distance in Czwartos’s approach – a distance he implicitly acknowledges – but not one that makes his involvement with the subject and his whole-hearted engagement with the topics any less true. This distance could mislead the viewer into considering his relation to the subject matter to be noncommittal. Such a view could be supported by the observation that his earlier paintings are playful and involved in the business of commenting upon art. In the Cursed Soldiers series, Czwartos does not flinch at the awful and profound. Czwartos has – without changing emotional register, style or compositional approach – “deepened the game”, as Francis Bacon put it. He has gone beyond art-about-art and taken as his subject the story of his nation and (by extension) the nature of man. One might say that Czwartos has now accepted his fate and become the Polish History painter that was always destined to be.

Ignacy Czwartos, We talked about Malevich (pl. Rozmawialiśmy o Malewiczu),

180x180 cm, oil on canvas, 2012-2013.

Czwartos, modern History painter

History painting is the genre in which an artist depicts significant persons and events from history, doing so to draw attention to the importance of the subject, in order to instruct the viewer and ennoble art. It is no mere illustration or excuse for dramatic content; it is a didactic moral activity, and therefore ranked as the pre-eminent field of art, alongside religious art. A History painter cannot absolve himself of the necessity of imparting a message, from which recent painters (in the epoch of ironical detachment) have often shied away. Czwartos is an artist notable for his wit but he is a powerfully effective History painter because he leaves us in no doubt about the seriousness with which he treats his subjects, not least the Cursed Soldiers and the individuals in religious orders who assisted them. Even the judges, guards and executors, are not free from Czwartos’s forensically acute yet compassionate eye.

Czwartos has solved the problem that faces any modern History painter, namely, how one can paint narrative accounts of a historical event in a language that is appropriate, effective, moving, articulate and yet not anachronistic. The artist’s debt to photographic sources is not hidden; his skill in abstract painting and an admiration for the effects of devotional painting and folk art has freighted his most recent paintings with extra layers of meaning. Czwartos speaks about history in ways that deploy historical devices (Nineteenth Century photographic presentation, religious art, folk art, forensic photographs); this process of incorporation, and the painter’s elective affinities, contribute to the complex presence and weight of the memorial paintings.

Czwartos as History moralist (a title he would perhaps feel ambivalent towards) can direct us towards pity, horror, condemnation, curiosity, anger and sadness, without sentimentality, and enjoin us to look, remember and meditate upon what we have been shown. He is sensitive to the nuances of history and the dark spaces which make we fear to approach. For a living painter to address modern history in a serious and instructive manner without making his own emotions – and his political stance – the subject of his art leaves many viewers wrongfooted and suspicious; that is precisely why Czwartos is a such a significant figure and likely to be considered a major artist of the Twenty-First Century.

Memorialising individuals who were motivated by faith, nationhood and politics to the extent of suffering and dying for those principles – unhindered by consideration of material progress and personal safety – forces us to consider our own character and behaviour.

For how do we, gazing upon those who died for their beliefs, assess our own failings in times of comfort and security? How can we not judge ourselves inadequate? The unquiet dead are unwelcome ghosts for Europeans; they pose acutely difficult questions for Poles.

One wonders what fate awaits Czwartos and his paintings in an era of renewed political turbulence in Poland and Europe more widely. Whatever lies ahead, Czwartos’s stark, ludic and painful images will retain their psychic charge and continue to touch a nerve deep within viewers. Seen in the light of his most recent art, Czwartos’s whole oeuvre now comes into focus as an extended multi-part pictorial Ars Moriendi, which describes how men can humbly acknowledge their debts, embrace their allotted role, die mindfully and meet their end in a manner that gives their lives added meaning and dignity.