“This time Balenciaga went too far!" — media hype, widespread outrage and, eventually, a nervous cover up ensued as a result of two marketing campaigns launched by the exclusive Spanish fashion house Balenciaga at the end of 2022[1]. The first of them, promoting Balenciaga Gift Shop line and presenting children surrounded by the brand products, was instantly accused of sexualizing the youngest. The other one, produced in collaboration with Adidas, featured photos in which a keen eye could spot documents of child pornography court cases, among others. A scandal broke out and a hashtag #CancelBalenciaga became popular on social media. Facing a major image crisis, the fashion house cancelled controversial marketing campaigns and sued the company that prepared one of them. Celebrities – including the ones associated with the brand – such as Kim Kardashian, expressed their outrage and everything came back to normal.

Could the fuss about Balenciaga, whose products are completely out of financial reach for both the author of these words and most of “Obieg” readers, inspire to reflect on the state of modern culture? I would like to try and offer some thoughts on the problem caused by the Spanish fashion house. In order to do so, I will present the “enlightened picture critique” by Mariusz Bryl that allows an art historian to be actively involved in concern for the common good which constitutes a basis of democratic society. Using this perspective, I will take a closer look at „what can be seen” in the photos promoting Balenciaga gadgets. The article will be concluded with quite subversive proposal taken from Trujące owoce trzeciej filozofii podejrzeń… [Poisonous fruit of the third philosophy of suspicions – translator’s note] by Jacek Breczka. Perhaps the world of fashion is not broken but represents sublimation of modern culture. Degeneration of reality around us reaches far deeper and concerns us all – not just a small group of exclusive brand’s clients.

***

On the ethical level of a picture’s critique, Mariusz Bryl postulates a perspective of “enlightened picture critique” that would aim at developing awareness of the audience[2]. We must add that the author does not think only about the art enthusiasts, but all people who are bombarded by the infinite number of images – in the press, TV, social media sites etc. In this interpretation, the methods known to art historians would not serve to describe or analyse artworks but rather to “dismantle” the media message which uses the image. The purpose of “enlightened picture critique” would be to create space to communicate for a given community and to raise awareness among its members as to what kind of manipulation mechanisms they are subjected to by art creators. Such a critical attitude of each of the citizens would then be a starting point for honest dialogue and political engagement, understood in classical, Aristotelian terms – as caring about the common good and seeking justice in public life.

Bryl presents sample analyses that use postulated perspective. Firstly, the author juxtaposes two media coverage of John Paul II last pilgrimage to his home country in 2002[3]. The first of these, published in “Life” magazine, was given a photo of the Pope walking down the stairs from the plane on his own. The other analysed photo was published in “Nie” weekly and it was an illustration to Jerzy Urban’s column Door-to-door sado-maso which happened to be a vulgar flame attacking the head of the Holy See. This photograph showed John Paul II rising his arm in greeting gesture and a priest standing nearby who is steadying the Pope by holding him by the sleeve of his cassock. A moment when the photograph was taken is most unfavourable for the presented figure. Like that, the chosen picture was supposed to be a visual “argument” in favour of Urban’s article disgusting words.

As for the second example, we are given the analysis of “Gazeta Wyborcza” front page, an issue published on December 3, 2008, specifically the article entitled Ich Watykan nie broni [They will not be protected by Vatican – translator’s note][4]. The text includes a photo showing the moment before the hanging of two Iranian homosexuals. According to the article, the Vatican representative to the UN had not signed the resolution against punishing homosexuals. In fact, the question of the document was far more complicated and controversial; its uncritical adoption would bring complex decisions of an ideological nature in the future. That was something “Gazeta Wyborcza” failed to mention. In his precise analysis, Bryl argues that the way the front page of the newspaper is arranged – with the strikingly suggestive photo – seems to imply that the Holy See should be burdened with moral responsibility for the tragic death of two Iranian young men. Thus, “Gazeta Wyborcza” journalist puts clergy on an equal footing with the tormentors of homosexuals and it does so without a shade of doubt.

The “enlightened picture critique” postulated by Bryl, with its use of insightful method and impartial way of observing visual messages seem to be a perfect tool to analyse Balenciaga’s scandalous campaign. The art historian’s closer look at the matter will help to break through the media hype and reveal what could be hidden behind the photos of children promoting Spanish fashion house’s latest collection.

Proponents of the paedophile scandal in the fashion house theory have an ace up their sleeve. It is the photograph from the second campaign which shows judicial documents on child pornography. Though the ambiguity here is difficult to notice, any kind of move involving this particular subject should be unequivocally denounced instead of being a part of the media game. What about the rest of the photos that were supposed to hit Balenciaga out of the lead position in the fashion world?

Jam Press/Balenciaga

The author of the photos used in the first marketing campaign (the one with children images) is Italian photographer Gabriele Galimberti – a regular collaborator of National Geographic magazine who published his works in “Le Monde”, “La Repubblica”, “Marie Claire”, to name a few. In 2021, the creator won the first World Press Photo Award in category Stories for portraits in The Ameriguns series. The winning entry presented Americans with their impressive gun collections. This idea was later expanded in Toy Stories where the photographer showed images of children from all over the world who proudly presented their toys. The artist’s idea gained interesting tension through the clash of children’s world and clear-cut social stratification which was indicated by the quantity and the character of toys different children owned.

This technique typical of Galimberti – showing the model surrounded by carefully arranged objects – is used in Balenciaga campaign as well. The context of photographer’s previous works implies that items placed are owned by the portrayed children. In other words: the youngest proudly present objects among which we could find pieces of clothing, shoes and accessories – including the ones that bring sexual connotation. But are we absolutely sure that this is not “the tongue always turns to the aching tooth” situation we are dealing with here? The art historian sobering perspective forces “what you see is what you get” interpretation of the presented scene and excludes precociously imposed own interpretation to demonstrate eventually stylistic measures typical of the artist: undifferentiated focus sharpness of the lens within the photo plane expressing each detail with equal precision and displaying an almost unreal order (for everyone who found themselves in a child’s room at least once – the last one is clear) of items arranged in the foreground. The majority of the shown accessories is by no means controversial. There are toys, everyday items, a bit of jewellery, pieces of clothing. Some of these items definitely belong to adults – yet, who among us did not dress up in clothes taken out from mom’s and dad’s wardrobe to perform a fashion show to the joy of the family, back when we were kids (and were not part of the idiotic trend of searching one’s gender identity but, instead, were just innocently having fun)?

Jam Press/Balenciaga

However, the biggest turmoil came with cuddly-bags, equipped with leather accessories straight from BDSM subculture[5], with black, ragged hair of a gothic rock star and wide open, shaded eyes. Some interpreted these as marks resulting from the characteristic trauma of molested kids. What appears to be bruises from the distance, turn out to be multicoloured irises of the fluffy teddy bears once zoomed in. We notice that all the cuddly toys of the series have both garnished with both BDSM-related and heavy metal and punk rock style – brads, chains, mohawks and earrings. These may not seem like ideal props for a photo session with kids, but Balenciaga cuddly toys feel more like popular rock stars, musicians of Kiss, Alice Cooper or Judas Priest than victims of sexual violence. That is what distinguishes Balenciaga teddy bear bags – that are, in fact, a snob gadget for adults, not a real toy – from immensely popular toy series for children called Monster High by Mattel that combined the look of a Barbie doll and characters from horror movies like werewolves, zombies, ghosts and vampires. A more recent example would be a Huggy Wuggy “cuddly toy”, a flavour of the month among the children that stormed toy shops and market stands with tacky Eastern products. It is an effigy of a furry blue creature, grotesquely baring its teeth, that is a character in Poppy Playtime, a video game for adults, where Huggy Wuggy hugs in order to kill the player’s character in a gruesome manner[6].

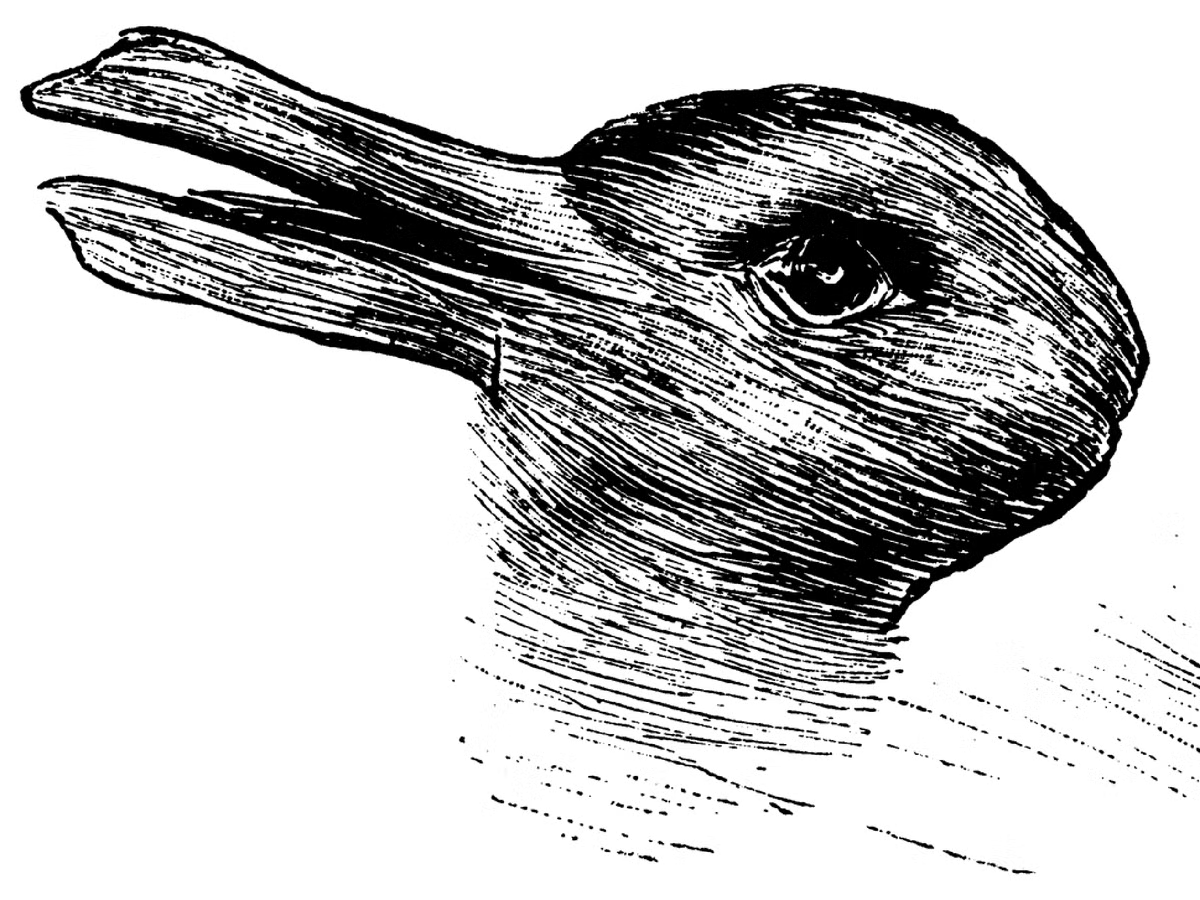

Looking at the photos of the Balenciaga campaign, a viewer discovers more traces that support the thesis about its scandalous content. There are black dragons on the walls, a reference to unholy powers. The red shoes of the boy become the devil snouts and there is a horned figure doodle on the drawing of the child. It seems that we are dealing with a rather characteristic feedback: a viewer stimulated by the suggestion follows numerous details in the photos and adds a hidden sense to them. Paying too much attention to symbols included in the portrayals – that lack firm anchoring in the structure of the picture or precisely established context – most often does not lead to anything constructive. In case someone has doubts, all it takes to dispel them is to open the famous Słownik symboli [The dictionary of symbols – translator’s note] by Władysław Kopaliński where everything can be linked to anything. Another general mechanism deluding the viewer in similar cases is the example of the “rabbit-duck” illusion used in the works of scholars such as Ludwig Wittgenstein and Ernst Gombrich. In this optical paradox, people observing it are able to see one or the other animal – and everyone is right.

Joseph Jastrow, Królikokaczka, 1899

It is not that the fashion house fell victim to conspiracy theories’ hunters. I am fully convinced that the creators behind the campaign deliberately used the ambiguity of message to fuel the interest in the topic. It is exemplified by a specific typo seen in one of the photos. The name of the brand – presented on a rolled tape – is spelled with double “A” and when placed at the right angle forms “BAAL” (the name of one of the most powerful demons in occultism). Of course, according to “rabbit-duck” principle, what we have here as well is just the name of the brand with a spelling mistake.

Let us sum up all the current comments on last year’s marketing activities by Balenciaga. A single prop – court documents on the case of child pornography – clarified both the interpretation of Balenciaga Gift Shop series promotion and the future collaboration with Adidas. In this context, the shooting style of Galimberti gained a disturbing overtone. Further arguments used by the advocates of the campaign’s perverse meaning are close to conspiracy hunting; the arguments raised become what viewers think they are. Undoubtedly, leading the viewers by the nose is part of a scheme designed by the authors of the advertisement. Galimberti photos of Toy Story series show children presenting their toys in front of the camera. Similarly, the analysed Balenciaga campaign features children who (with the help of fashion house products) show what their world looks like: filled with ugliness and grotesque rather than serenity and beauty, pulsing with sexual content and aggressive message that children are seldom aware of. The reality of kids – with the consecutive, often cruel, fashions, “challenges” as well as incessant use of smartphones, social media and the unlimited access to pornography – is not at all different from the vision presented in Balenciaga’s advertisement. As such, the controversial advertisement should be raising awareness of concerned parents more than provoking outrage.

***

The creators of Balenciaga campaign trap their viewers in a moral snare proving just how effective this form of marketing can be. A number of people, though not interested in the Spanish fashion house offer and despite their outrage, do pass the controversial advertisement further and repeat the brand name time and time again. The fundamental message coming from the campaign – apart from establishing the name of the brand in the mind of the viewer – is related to the belief that fashion society, celebrity world and widely understood “the people upstairs” are degenerated. “The righteous indignation” caused among the recipients of Balenciaga advertisement results from discovering implicitly reprehensible content in its message – but in essence, it is a psycho-hygienic measure for us all. This mechanism is presented by Jacek Breczko in his article Trujące owoce trzeciej filozofii podejrzeń…[7]. The author attempts to show the effects of psychoanalysis by showing the pansexual nature of Freudianism and the sexualisation of human relationships. Psychotherapists using Sigmund Freud’s theory based their practice[8] on discovering the unconscious sexual drives in their patients. The mechanism of “denial” was of key importance here – it was only the psychoanalyst who was able to bring out “the real” memories of the treated individual that often turned out to be the fantasy of the very therapist performing the therapy[9]. In the 1970s, Freudianism was taken over and widely used by feminist movements which significantly altered its theoretical premise. They pointed molesting in their childhood as a source of failures in their adult lives[10]. Thanks to findings of psychoanalysts who “brought” patients’ suppressed memories, it was possible to present the disturbing statistics on sexual violence against minors. The general conclusion drawn from such an analytical practice was as follows: we are all monsters for whom abusing children is a way to treat own insecurities[11].

“But I am not like that at all” – a majority of us would think. The clear discrepancy between the results of the study and life experience generated tons of suspicion. If statistics were that high, we would be passing paedophiles on the streets every day. We must then stay alert – any kind of affection towards a child should raise our distrust[12]. And from here, we are just a step away from being suspicious of caretakers and children’s educators. Said suspicion is being fuelled by the media reporting cases of parental abuse towards their own children, celebrities that suddenly recall being molested decades ago or (a favourite subject of left-liberals) sexual abuse of the clergy.

I dare to say after Breczko, that the media message on paedophilia do serve one social role – paradoxically, they improve our mental comfort[13]. This view, as outrageous as it might be, becomes clear when looking at the issue from a more distant perspective. The world deprived of ethical foundation, where the only moral law is to avoid suffering and pursue pleasure and hurting children is red-flagged as absolute evil. In the face of galloping relativism, paedophilia assumed the role of a peculiar diabolus ex machina – a monster jumping out of the box, an argument that instantly finishes any discussion. We can treat our complexes this way. Maybe we are not perfect, but compared to those beasts hurting children we appear as angels. The crux of this ethical discussion that shape the culture is marginalised in social discourse since, in reality, the deviation of paedophilia concerns a fraction of the population. The information about scandals, including Balenciaga’s controversial campaign, place us on the same side of the barricade. The rightful side of it.

The campaign of the Spanish brand caused great uproar that, in my opinion, was an operation planned by marketing specialists. I am doubtful whether the last year’s scandal would cause a permanent decline in Balenciaga’s popularity or weaken its position in the world of fashion. As the vulgarisation and sexualisation of the culture continue, Galimberti photographs are nothing special. Moreover, materials from the controversial advertisement allow us to feel better by making us feel (though it is a stretch) morally superior. Last but not least, as a damage control measure, the company decided to collaborate with National Children’s Alliance foundation that promotes mental health and safety of the young. Demna Gvasalia, a creative director of the fashion house, apologised for his negligence and assured that his task was to “provoke thought”[14]. It would appear that, at least in my case, the assumptions of the campaign were successful.

[1] Ch. Binkley, M. Shoaib, Balenciaga: Cena prowokacji, (access for May 2, 2023); A. Stankiewicz, Balenciaga w ogniu krytyki. Co wiemy o skandalicznej kampanii z udziałem dzieci? (SUMMARY), (access for May 2, 2023/0.)

[2] M. Bryl, Etyczny wymiar krytyki obrazu, w: Historia sztuki dzisiaj. Materiały LVIII Ogólnopolskiej Sesji Naukowej Stowarzyszenia Historyków Sztuki. Poznań 19-21 listopada 2009, ed. J. Jarzewicz, J. Pazder, T. J. Żuchowski, Warszawa 2010, p. 47-62.

[3] Ibidem, p. 51.

[4] Ibidem, p. 53-60.

[5] Generally speaking, related to sadistic or masochistic behaviour. To find more information on the topic – see external sources.

[6] G. Gajkoś, Potwór z gry przytula, by zabić. Huggy Wuggy zyskuje popularność wśród dzieci, (access for May 2, 2023).

[7] J. Breczko, Trujące owoce trzeciej filozofii podejrzeń (O szkodliwym wpływie psychoanalizy na kulturę współczesną), (access for May 2, 2023).

[8] I intentionally use past tense here as, to the best of my knowledge, the psychoanalysis understood in Freudian terms now represents a relic of psychotherapy.

[9] J. Breczko, op. cit., p. 8.

[10] Ibidem.

[11] Ibidem, p. 9.

[12] Ibidem, p. 12-13.

[13] Ibidem, p. 10.

[14] A. Stankiewicz, op. cit.